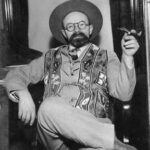

November 24, 1925 –

By Judy and Susan Ohmer, daughters

Gloria Lucille Anderson arrived in Petersburg on April 28, 1949, aboard an Alaska steam ship for a two-week visit with friends. By the time she was to return to Everett, Washington, 14 days later, she had already decided that “this was her spot,” and she’d taken a job. She said,

“I loved Alaska. It offered opportunity – and the exhilaration of possibility. It was a land of extremes and of characters. I felt as if I were coming home for the first time.”

Born in Chicago, November 24, 1925, Gloria started Kindergarten in Everett, Washington, as the Great Depression began. It was, she said, a time of incredible struggle, of heartache, of sadness, loss, and hunger. But somewhere in a child’s view of life, she learned to look for the good around her, and this viewing point sustained her through many challenges for the rest of her life

Both her parents worked. She came home to an empty house, built a fire, started dinner, and watched over her little brother. She dreamed of a home filled with laughter and warmth, with someone to greet her and be interested in her day. This colored her life and propelled her into many ventures, among them the trip to Alaska.

Opportunity on the “Last Frontier” presented itself immediately. Gloria wasn’t familiar with the work she was first asked to do, but said, “I could probably do that.” And with that, guessing she could probably do something became her words to life by as she went from opportunity to opportunity.

Her first job was as cook in a remote construction site where the city was installing new transformers at the hydroelectric plan. She bought the only cookbook she could find, purchased eights months of groceries, and flew to Blind Slough. She cooked there from April through November, learning to bake bread and feed a hungry crew.

After six months at the camp where Joy of Cooking was her Bible, Gloria returned to Petersburg. She accepted other work, from clerking at Electro Service, to sketching mink and doing autopsies at a fur farm, and working in the post office.

“I continued to be inspired by the rugged frontier and the chance to carve out a life of my own making.”

One morning while she was putting in a window display at Don Pettigrew’s service store, there was a tap on the window. She turned around to find a man making a face at her. Dave Ohmer later came in to apologize; he’d thought she was someone else. They began a friendship that deepened. Their dates included dancing at the old Elks Club, digging clams, playing cards with DeBoers and Pettigrews, and hunting. Of these family stories, her children believed she’d once climbed into the cavity of a moose to stay warm, but she later claimed she had only used ducks for mittens.

She says of her life after marriage that she chose to “focus on raising our five children, keep books for the cannery, and do charitable and community service work,” noting that Petersburg didn’t have social service such as orphanages/foster homes or alcoholic treatment programs, meals-on-wheels, humane societies, domestic violence shelters, etc. “People needed to help people.” Gloria was what she considered to be a “behind-the-scenes worker” who supported others to a healthier, happier life. But she was also a leader, an initiator of ideas, a woman of big heart. “Our home was always open and was usually very full.” Indeed, her children were accustomed to steeping over sleeping bodies in the livingroom on many mornings.

She and Fran Lund headed up the Alter Society’s December bake sale, the primary fundraiser for St. Catherine’s Catholic church, a mission church at the time. Their baking began in October. Lefse, fattigman, krumkaka, sunkaka, hjortatak, Berliner kranse, and rosettes, were among the many Norwegian specialties that filled the huge tins and vats in their kitchens. They also pickled herring, and they baked Swedish limpa and stollen for the popular event.

Her hands have always been busy. The Norwegian baby sweaters she knitted were legendary. Her first quilt won the top prize at the State Fair. She embroidered, beaded, arranged flowers, wove baskets, and created a colorful garden. She also liked to pound down walls, build cabinetry, and turnwooden bowls. While many children think their moms can heal boo-boos with a kiss, Gloria’s kids were witness to near miraculous healings–hamster resuscitations and gold fish revivals occurred with regularity, with solemn funerals being attended when the pet was beyond even her ability to cure. Any creature—human, furred, or finned—who crossed the threshold of Gloria’s home and stayed for more than 15 minutes was, literally, family. She was unofficial keeper of statistics at the high school basketball statistics, even when she didn’t have a child on the court. She enjoyed reading poetry, novels, and cookbooks. She has always been busy bringing in and putting up the harvest – cranberries, clams, rhubarb, and other Alaskan bounty.

Hospitality was basically Gloria’s middle name. She is highly regarded for her cooking talents – from Alaskan seafoods to international menus, as well as family favorites. A birthday treat was a dinner of your choice, where she was known for such selections as her teriyaki chicken, halibut cheeks, buttermilk biscuits, and split pea soup. She was a magician in making do, innovating, and stretching things to go around—her “poor man’s sukiyaki” could feed a dozen people with a head of cabbage and a pound of hamburger.

Gloria was musical, but when asked about it she said she just “Played for my own amazement.” She began in grade school with treble cleft instruments: e flat alto horn, trombone, and c-soprano sax. In high school she played bassoon in concert and glockenspiel in marching band. It was during her solo in “Grand Canyon Suite” that she learned it didn’t work to chew gum and play a reed instrument. As an adult she played ukulele, harp, piano, organ, and banjo. She became the organist at St. Catherine’s Catholic Church by what she called accident. She currently stars on base washtub in the Petersburg’s Norwegian kitchen band, the Lefse Marching Band.

In 1970 she and her sister-in-law Patti Norheim purchased the old Ben Franklin and renamed it The Cache. It became the heart of downtown, and the place to get everything from house wares to office supplies, toys to red-eared turtles and tourist items, fabrics to framed Rie Munoz artwork. It was a key community social center; a friendly place to stop for coffee from the back room, encouragement, or to duck in out of the rain. At the front of the store they served popcorn in “Hungry” and “Starving” sizes. On the rare summer days it didn’t rain, a sign was posted, “Closed for Sunshine,” and folks gathered at Blind Slough for picnics and jumping off the bridge. And they would specially open the store whenever the ferry from Kake docked.

Then in 1980 she bought controlling interest in the Tides Inn. It was a proud moment when the bank loaned her, a woman, a million dollars for the immediate expansion of the motel. “When I added the conference room and commercial kitchen it brought the ‘hearth and ‘living room’ to the business. The Tides Inn feels like an extension of who I am and how I believe in living life. It’s as if I have a big home to open, that is warm and welcoming to guests who happen by. I feel like I’m finally living my childhood dream.”

Gloria won several State awards for tourism and her work at increasing visitorship and commerce to the area. She developed a local Elder Hostel program, and worked with Cruise West on creating southeastern tours. “Living in Petersburg allowed me to do that,” she said, “People were supportive of whatever you wanted to do. Nothing seemed too far-fetched.” Gloria’s life work has been written up in the nation’s largest newspapers, and she never told a soul.

Gloria was widowed in 1979. “Busyness has always helped me work through my pain,” she said, “I thought I needed to be buy 36 hours a day instead of just 20.” Her spiritual beliefs sustained her, as did her philosophy of looking for the good and for the opportunity in every day.

She remarried in 1996 to Don Koenigs, a neighbor and fellow church member who had recently lost his wife to cancer.

She and Dave Ohmer had five children: Judy, David, Becky, Penny (Katelyn), and Susan. She raised her children on the “Bambi rule” (“If you don’t have anything nice to say, don’t say nothin’ at all.”), and the concept that “something good could still happen before midnight.”

“But what I have most sense of legacy about, are my children. Each has gone on to be successful in what they’ve chosen to do. Each has a college education, among them a Ph.D. and two Masters degrees, which is quite an accomplishment coming from a rural, isolated setting where they’d never even seen a college or university. Each has a sense of business and of working with people. I see them opening their homes and laying out the welcome mat. And my childhood dream is perpetuated.”

|

|

Leave a reply